Form and Variation in Balinese Village Structure

CLIFFORD

GEERTZ

Center for Advanced Study in the

Behavioral Sciences

As ALL things Balinese, Balinese villages are peculiar, complicated, and extraordinarily diverse. There is no simple uniformity of social structure to be found over the whole of the small, crowded countryside, no straightforward form of village organization easily pictured in terms of single typological construction, no "average" village, a description of which may well stand for the whole. Rather, there is a set of marvelously complex social systems, no one of which is quite like any other, no one of which fails to show some marked peculiarity of form. Even contiguous villages may be quite differently organized; formal elements--such as caste or kinship--of central importance in one village may be of marginal significance in another; and each of the twentyfive or so villages sampled in the Tabanan and Klungkung regions of south Bali in 1957--a total area of only some 450 square miles--showed important structural features in some sense idiosyncratic with respect to the others.1 Neither simplicity nor uniformity are Balinese virtues.

Yet all these small-scale social systems are clearly of a family. They represent variations, however intricate, on a common set of organizational themes, so that what is constant in Balinese village structure is the set of components out of which it is constructed, not the structure itself. These components are in themselves discrete, more or less independent of one another: the Balinese village is in no sense a corporate territorial unit coordinating all aspects of life in terms of residence and land ownership, as peasant villages have commonly been described, but it is rather a compound of social structures, each based on a different principle of social affiliation and adjusted to one another only insofar as seems essential. It is this multiple, composite nature of Balinese village structure which makes possible its high degree of variation while maintaining a general formal type, for the play between the several discrete structural forms is great enough to allow a wide range of choice as to the mode of their integration with one another in any particular instance. Like so many organic compounds composed of the same molecules arranged in different configurations, Balinese villages display a wide variation in structure on the basis of a set of invariant fundamental ingredients.

Perhaps the best systematic formulation of this type of village structure is to conceptualize it in terms of the intersection of theoretically separable planes of social organization. Each such plane consists of a set of social institutions based on a wholly different principle of affiliation, a different manner of grouping individuals or keeping them apart. In any particular village all important planes will be present, but the way in which they are adjusted to one another, the way in which they intersect, will differ, for there is no clear princi pIe in terms of which this intersection must be formed. The analysis of village structure therefore consists in first discriminating the organizational planes of significance and then describing the manner in which, in actual fact, they intersect.

In Bali, seven such planes are of major significance, based on: (1) shared obligation to worship at a given temple, (2) common residence, (3) ownership of rice land lying within a single watershed, (4) commonality of ascribed social status or caste, (5) consanguineal and affinal kinship ties, (6) common membership in one or another "voluntary" organization, and (7) common legal subordination to a single government administrative official. In the following paper, I will first analyze each of these planes of organization, then describe three villages as examples of differing modes of intersection of these planes, and finally offer a discussion of some of the theoretical implications of this type of village organization.

PLANES OF SOCIAL ORGANIZATION

1. Shared obligation to worship at a given temple.

Bali is a land of temples. One sees them everywhere--under the village banyan tree, in the midst of rice fields, by waterfalls, in the centers of large towns, by a graveyard, at the sea edge, on a lake island, in every houseyard, at the mountain top--everywhere; of all sizes and in all conditions of repair; all or most showing the traditional form: the high brick walls, the intricately carved split gate, the tall pagodalike altars with their storeyed thatched roofs.2 And there are no ruins in Bali: to each of these thousands of temples there is attached both an hereditary priest and a definite congregation of worshipers obligated to perform detailed ritual activities within its walls at fixed intervals, most commonly every six months. Such a congregation is said to njungsung the temple--literally to carry it on its head, as women carry nearly everything in Bali, including the elaborate offerings they bring to the temples on festival days.3 Every family in Bali, unless it be Christian or Moslem, carries at least a half dozen templescalled pura--on its head.

Of the great variety of pura, by far the most important to the Balinese are the Kahyangan-Tiga. Kahyangan is an honorific word for temple (meaning literally "place of the gods"), indicating a pura of unusual importance, and tiga means three--thus, "the three great temples." There are probably over a thousand sets of such temples in Bali, with membership ranging from fifty up to several thousand families; the three temples concerned in any particular locality are the Pura Puseh, or origin temple, theoretically the temple built at the time of the first settlement of the area; the Pura Dalam, or graveyard temple for the spirits of the local dead; and the Pura Balai Agung, or "great council temple" (of the gods), dedicated primarily to maintaining the fertility of the surrounding rice fields. At the first two of these temples festivals are held once in every 210--day Balinese year, at the third once in a lunar year, the specific days depending upon the tradition of the individual temples. At such festival times the gods are conceived to descend from heaven, remain for three days, and then return to their home, and the congregation is obligated to entertain them during the time of their stay by means of complex offerings, elaborate rituals, and skillful artistic performances under the general direction of the temple priest and the secular head of the temple. The cost of the festivals, the rather large amounts of labor involved, and the general upkeep of the temples falls on each member of the congregation equally, and this group is typically organized in some fairly complicated manner to achieve these ends.

As mentioned, Kahyangan- Tiga membership is defined territorially, each Balinese belonging to just one of the sets. Nevertheless, one cannot say, as have most scholars, that he belongs to the temple of his "village," and thus that Kahyangan- Tiga can be translated "the three village temples," because only in the limiting case are the boundaries of the basic territorial political unit, here called the hamlet, and of the Kahyangan- Tiga congregation coterminous; in most instances, the religious and political units are not coordinate but cross-cut one another. Whatever the Balinese village mayor may not be, it is not simply definable as all people worshiping at one set of Kahyangan-Tiga, because people so obligated to worship commonly form a group for no other social function--political, economic, familiar, or whatever. The congregation of the Kahyangan-Tiga is, in essence, a specifically religious body; in most cases it comes together only at the obligatory temple festivals.4 Thus, the oft-repeated and much-loved rites at these temples serve to form one crucial bond among rural Balinese of a generally territorial sort, but this bond balances off against other bonds formed in terms of more concretely social activities rather than, as is typical of religious ties, directly reinforcing them.

Besides the Kahyangan-Tiga there are dozens of other types of temples, with different bases in terms of which their congregations are formed: there are ricefield temples, at which worship the men who own land within a particular irrigation society; there are kinship temples, supported by members of a single patriline; there are caste temples where only people with a given rank worship; there are associational temples formed on a voluntary companionate basis, their obligations being inherited by their descendents; there are state temples attended by people subject to a single lord, and so on. Again, some of these correspond to concrete social groups with other, nonreligious purposes, some do not; some are almost inevitably found, some but rarely; some are obligatory for all men, some are voluntary. Thus, by plotting temple types in a locality, one plots the general shape of the local social structure but not its specific outlines. The temple system of the Balinese countryside forms a relatively fixed stone and wood mold in terms of which rural social organization expresses itself, and the semi-annual festivals in each temple dramatize the sorts of ties out of which Balinese peasants build their collective life. But it does not stamp that life into any simple or unvarying form, for within the general mold the possibilities for variations in stress, combination, and adjustment of social elements seem almost limitless.

2. Common Residence.

As most Indonesians, Balinese live in a clustered settlement pattern, their walled-in house-compounds jammed against each other in an almost urban fashion so as to conserve rice-land in the face of tremendously dense and growing population.5 Within such clusters the basic territorial political unit is the hamlet, or band jar. Bandjar, which mayor may not be spatially isolated, depending upon the size of the settlement, contain anywhere from a dozen to several hundred nuclear families, averaging perhaps about eighty or ninety. In most parts of Bali, the bandjar may be rather simply defined as all those people subject to the decisions taken in one hamlet meeting house, or bale band jar. Bandjar meetings of all male household heads are usually held in this bale once in a 35-day Balinese month, at which time all important policy decisions for the hamlet as a corporate unit are made, mainly by means of a "sense of the meeting" universal agreement process. As the temple is the focus of the religious community, so the meeting house--a wall-less, peaked-roof, Polynesian-looking structure usually located in the center of the hamlet--is the focus of the political community.6

To the bandjar are allocated the sort of general governmental and legal functions common to peasant communities in most parts of the world. It is responsible for local security, for the legitimation of marriage and divorce and the settlement of inheritance disputes, and for the maintenance of public works such as rural roads, the meeting house, and the local market sheds and cockpit. Commonly it will own a gamelan orchestra and perhaps dancing costumes and masks as well. As in many, but not all parts of Bali, house-land is corporately owned by the bandjar as a whole, the hamlet also may regulate the distribution of dwelling places, and so control immigration. For serious crimes it may even expel members, confiscating their house-land and denying them all local political rights--for the Balinese the severest of social sanctions.

The hamlet also has significant tax powers. It may fine people for infractions of local custom, can demand contributions for public entertainments, repairs to civic structures, or social welfare activities more or less at will, and can exercise the right to harvest all rice land owned by bandjar members--the members as a whole acting as the harvesters--for a customary share of the product. Consequently, most bandjar have sizeable treasuries and may even own rice land, purchased out of income, the proceeds of which are also directed to public purposes. Nowadays, a few bandjar even own trucks or buses, others help finance local schools, yet others erect cooperative coffee shops.

Finally, the bandjar also acts as a communal work group for certain ritual purposes, especially for cremations, which, along with temple festivals, are still the most important ceremonies in Bali, although their size and frequency have been reduced somewhat in the years since the war.7 When an individual family decides to cremate, all members of the bandjar are obligated to make customary contributions in kind and to work preparing the offerings, food, and paraphernalia demanded for as long as a month in advance. Similar cooperation, but of lesser degree, is often enjoined for other rites of passage, such as tooth filing, marriage, and death. The bandjar is thus at once a legal, fiscal, and ceremonial unit, providing perhaps the most intensely valued framework for peasant solidarity.

The heads of the hamlet are called klian, literally "elder." In some bandjar there is but one, most often two or three. Sometimes there are as many as four or five, usually reflecting either a large bandjar or one sharply segmented into strong kin or other subgroups, in which all important cross-cutting minorities must be given a role in bandjar leadership. Nowadays klian are usually elected for five years and then replaced by a new set, often chosen by the outgoing group with the approval of the bandjar meeting, so as to avoid electioneering. Klian are assisted by various lesser officials, whose jobs are usually rotated monthly among the members of the bandjar. Though the klian lead the discussion at the bandjar meeting, hold the public treasury, direct communal work, and commonly are men of some weight in the local community they are not possessed of much formal authority. In line with the general Balinese tendency to disperse power very thinly, to dislike and distrust people who project themselves above the group as a whole, and to be very jealous of the rights of the public as a corporate group, the klian are in a very literal sense more servants of the bandjar than its masters, and most of them are extraordinarily cautious about taking any action not previously approved in the hamlet meeting. Klian, who are unpaid and have no special perquisites, feel that their position mainly earns them the right to work harder for the public and be more abused by it; wearily, they compare their job to that of a man caring for male ducks: like the drake, the bandjar produces lots of squawks but no eggs.

3. Ownership of rice land lying within a single watershed.

Unlike peasant societies in most parts of the world, there is in Bali almost no connection between the ownership and management of cultivable land on the one hand and local political (i.e., hamlet) organization on the other. The irrigation society, or subak, regulates all matters having to do with the cultivation of wet rice and it is a wholly separate organization from the bandjar. "We have two sorts of custom," say the Balinese, "dry customs for the hamlet, wet ones for the irrigation society."

Subak are organized according to the water system: all individuals owning land which is irrigated from a single water source--a single dam and canal running from dam to fields--belong to a single subak. Subak whose direct water sources are branches of a common larger dam and canal form larger and less tightly knit units, and finally the entire watershed of one river system forms an overall, but even looser, integrative unit. As Balinese land ownership is quite fragmented, a man's holding typically consisting of two or three quarter- or half-acre plots scattered about the countryside, often at some distance from his home, the members of one subak almost never hail from a single hamlet, but from ten or fifteen different ones; while from the point of view of the hamlet, members of a single bandjar will commonly own land in a large number of subak. Thus as the spatial distribution of temples sets the boundaries on Balinese religious organization, and the nucleated settlement pattern forms the physical framework for political organization, so the concrete outline of the Balinese irrigation system of simple stone and clay dams, mud-lined canals and tunnels, and bamboo water dividers provides the context within which Baliese agricultural activities are organized.

Though organizational details and terminology differ widely from region to region, there are elected chiefs--usually called klian subak, as opposed to klian band jar--over the subak, while the higher levels of watershed and river system organization are coordinated by appointed officials of the central government as the heirs of the traditional irrigation and tax officials of the old Balinese kingdoms. But, again, it is primarily the subak as a whole which deermines in the light of its inherited traditions, its own policies.

The subak is responsible for the maintenance of its irrigation system, a task involving almost continual labor, for the apportionment of water among members of the subak, and for the scheduling of planting. It levies fines for infractions of rules (stealing water, ignoring planting directives, shirking work, and so on), maintains the subak temples and carries out a whole sequence of ritual activities connected with the agricultural cycle, controls fishing, fodder gathering, duck herding and other secondary activities in the subak, and so on and so forth. In most of the larger subak today the actual irrigation work--the constant repair of dams and canals and the perpetual opening and closing of water gates involved in water distribution--is carried out by only a part of the subak membership, called the "water group," which then receives a money payment from those not so working, the amount again being determined by the subak as a whole. Complex patterns of share tenancy, involved systems of controlled crop rotation, varying modes of internal subak organization, and the increasing efforts by the government water officials to improve inter-subak coordination complicate the whole picture. But everywhere the status of the subak as an independent, self-regulating, corporate group with its own rules and its own purposes remains as unchallenged today as it was in the times of the Balinese kings.

4. Commonality of ascribed social status.

The Balinese, like the Indians from whom they have borrowed (and reformulated) so much, have commonly been described as having a caste system. They do, in the sense that social status is patrilineally inherited, that marriage is fairly strictly regulated in terms of status, and that, save for a few unusual exceptions, mobility between levels within the prestige system is in theory impossible and in practice difficult. But they do not in the sense of possessing a ranked hierarchy of well-defined corporate groups, each with specific and exclusive occupational, social, and religious functions all supported by elaborate patterns of ceremonial avoidance and commensality and by a complex belief system justifying radical status inequality. Were the term "caste" not so deeply ingrained in the literature on Bali, it might be less confusing to speak of the Balinese as having a "title system," for it is in terms of a set of explicit titles, passing from father to child and attached to the individual's name as a term both of address and reference, that prestige is distributed.

Following Indian usage, the Balinese divide themselves into four main groups: Brahmana, Satria, Vesia, and Sudra. Since in such a classification more than 90 per cent of the population falls into the fourth category, a more common division for everyday use is made between Triwangsa ("the three peopIes"), the first three groups taken as a unit, and the Sudra, which in a broad and not altogether consistent way corresponds to the gentry--peasantry distinction common to nonindustrial civilizations generally. Each group is then subdivided further in terms of the title system, the actual basis of the individual's rank in the society. Given a sample list of titles--Ida Bagus, Tjokorda, Dewa, Ngakan, Bagus, I Gusti, Gusti, Gusi, Djero, Gde--any but the most uninformed Balinese could tell you they were placed in a generally descending order of status, but only a small minority of theorists could tell you that the first was a Brahmana title, the next four Satria, the next three Vesia, and the last two Sudra.8 In making status distinctions a man thinks and talks in terms of titles, not in terms of caste.

In general, a man may marry anyone of the same title or lower, a woman anyone of the same title or higher--thus hypergamy. In pre-Dutch times (i.e., before 1906, for South Bali only came under direct Dutch control at the beginning of this century) miscaste marriages were punished by exile or--particularly in the case of a Triwangsa girl and a Sudra man--death. Even today a girl marrying down is commonly "thrown away" by her family, in the sense that she is no longer recognized as kin and all social intercourse between her and her parents ceases. Under modern conditions such breaches often heal after some years have passed, particularly if the mismatch is not too great; but miscaste marriages are in any case very rare even today.

As the number of Triwangsa is so much less than the number of Sudra, status regulation of marriage means that the patterns of affinal connection tend to work out rather differently for the two groups, in that most Triwangsa marriages are hamlet exogamous, i.e., interlocal, while most Sudra marriages are hamlet endogamous, i.e., intralocal. This contrast lifts the horizontally linked Triwangsa up as a supra-hamlet all-Bali group over the highly localized Sudra; a pattern congruent, of course, with the fact that the Triwangsa almost completely monopolized the interlocal, superordinate political and religious roles of the traditional Balinese state structure, as they do today of the Balinese branch of the Indonesian civil service.

The caste (or title) composition of any given hamlet (or temple group, or irrigation society) varies very widely. In one locality one may find representatives of a wide range of titles in a smooth gradient from the highest to the lowest, in another only very high and very low ones, in a third only middle range or only very high ones, in a fourth nothing but Sudra, and so on. And, as caste is a crucial factor in both political and kinship organization, such differences entail important differences in social structure. Prestige stratification in Bali is a powerful integrative force both on the local and on the islandwide levels.

5. Consanguineal and affinal kinship ties.

Descent and inheritance are patrilineal in Bali, residence is virilocal, but kinship terminology is classic Hawaiian--i.e., wholly bilateral and generational. The major exception to patri-descent and residence is that a man who has no sons may marry a daughter uxorilocally and designate her as his heir; her husband abandons his rights in his own patriline, as a woman does at marriage in the normal case, and moves to his wife's home to live. As this almost always occurs in cases where male heirs are lacking, Balinese genealogies show a noticeable ambilineal element, in that a certain percentage of the ties are traced through women rather than men.

The basic residential unit is the pekarangan or walled house compound, which in kinship terms may house groups which range from a simple nuclear family up to a three or more generation extended patri-family. Typically two or three nuclear families, often with various unattached or aged patri-relatives, occupy a single pekarangan, but occasionally compounds with as many as ten or fifteen families, related through a common paternal grandfather may be found, particularly among the upper caste groups. In addition to being a residential unit, the compound is a very important religious unit, for each compound group supports a small temple in the northeast corner of the yard dedicated to its direct ancestors at which twice yearly ceremonials must be given. Finally, the compound is usually divided into kitchens, called kuren, typically one nuclear family to a kitchen, but sometimes two or three, and it is this kitchen group which is the basic kin unit from the point of view of all superordinate social institutions: it is the kuren which is taxed for the Kahyangan-Tiga temples, which is allotted a seat in the meeting house, which must send a worker to repair the dam or participate in the harvest, which is the rice-field owning unit, and so on.

Above the compound and the kitchen one commonly finds, within any given hamlet, from one to ten or so (largely but not entirely) endogamous corporate kin groups called dadia.9 Such dadia are basically ritual units, but they may also act as collective work groups for various social and economic tasks, may provide the main framework for informal social intercourse outside the immediate family for its members, may serve as an undivided unit in the local stratification hierarchy, and may form a well-integrated faction within the general hamlet political system. The degree to which it takes on these general social functions differs rather widely from village to village. In some villages dadia organization is the central focus of social life, the axis around which it revolves; in others it is of relatively secondary importance; and in a few villages, especially semi-urbanized ones, dadia may not exist at all.

Rarely is the whole hamlet population organized into dadia, and sometimes only a definite minority will be. This is so because of the manner in which dadia are formed. When a family line begins to grow in size, wealth, and local political power, it begins to feel, as a consequence of what is probably the central Balinese social value, status pride, a necessity for a more intensified public expression of what it takes to be its increased importance within the hamlet. At this point the various households which compose the line will join together under a chief elected from …among them to build themselves a larger ancestral temple. This temple will usually be built on public, hamlet-owned land, rather than within the confines of one of the houseyards, thus symbolizing the fact that the line has come to be of consequence in the jural-political domain as well as in the domestic. The semi-annual ancestor worship ceremonies the group carries out now become more elaborate, stimulated, as is the building and (as the group continues to grow in power, size, and wealth) periodic renovation of the temple itself, by status rivalry with other local dadia.

Often within the large dadia, subgroups have differentiated and become corporate groups in their own right. These sub-dadia (the Balinese refer to them by a variety of terms) are composed of members of the dadia who know or feel themselves rather more closely related to one another than to the other members of the dadia. Even when there are sub-dadia, not all members of the dadia will necessarily belong to one of them. Sometimes a majority will remain free-floating dadia members and will have no sub-dadia ties at all. In one large dadia, for example, there were five sub-dadia accounting for sixty of the eighty or so kitchens in the dadia, the other twenty having no sub-dadia membership. It is the dadia, not the sub-dadia, which is the fundamental group, though the latter also often takes on important social functions.

As noted, the particular functions allocated to kin groups varies from place to place and the integration of these groups with each other and with the other social institutions becomes complex. Also, the number and relative size of kin groups in a given hamlet makes a notable difference in how both the kin groups themselves and the hamlet function. A hamlet with, say, one large dadia and four small ones, will differ in both organization and operation from one with three medium large ones plus one or two small ones, or with five or six of roughly equal size. Such issues cannot be pursued here, but it should be clear that kinship, rather than shrinking to a concern with primarily "familial" matters as tends to occur in many peasant societies, remains in Bali an important organizing force in the society generally, albeit but one among many such forces.

6. Common membership in one or another voluntary organization.

The Balinese term for any organized group is seka; literally, "to be as one." Thus the group of hamlet people is called the seka band jar, the irrigation group is called the seka subak, and there are seka dadia, seka pura, and so on. But beyond these formal, more or less obligatory groups, there are thousands of completely voluntary organizations dedicated to one or another specific purpose, which are just called seka. These cross-cut all other structural categories and are based wholly on the specific functional ends to which they are directed.

There are seka for housebuilding, for various kinds of agricultural work, for transporting goods to market, for music, dance, and drama performances, for weaving mats, moulding pottery, or making bricks, for singing and interpreting Balinese poetry, for erecting and maintaining a temple at a given waterfall or a particular sacred grove, for buying and selling food, textiles or cigarettes, and for literally dozens of other tasks. Many bandjars have seka for such highly specific purposes as hunting coconut squirrels or building simple ferris wheels for holiday celebrations. Such voluntary seka may have a half dozen or a hundred members, they may last for several weeks or for years, the sons inheriting the fathers' memberships. Some of them build up quite sizeable treasuries and profits to divide among the members, some have yearly feasts of celebration, others even lend their earnings at interest.

As seka loyalty is a major value in Balinese culture, these voluntary groups are not just peripheral organizations but a basic part of Balinese social life. Almost every Balinese belongs to three or four private seka of this sort, and the alliances formed in them balance off those formed in the more formally organized sectors of Balinese social structure in the complex cross-cutting social integration characteristic of the island. From one point of view, all of Balinese social organization can be seen as a set of formal and voluntary seka intersecting with one another in diverse ways.

7. Common legal subordination to a single government administrative official.

In addition to hamlet, irrigation society, and Kahyangan- Tiga temple organization, there is another sort of territorial unit at the rural level which stems from the organization of the Indonesian governmental bureaucracy as it reaches down into the Balinese countryside. This is the perbekelan, so called because it is headed by an official called a Perbekel. Before the Revolution the Perbekel was appointed by his Colonial superiors; since it, he is elected by his constituency. He still serves until either he retires or a movement to unseat him develops. He is always a local man, in most cases set apart from his neighbors only in having somewhat more education (although in line with the traditions of Balinese statecraft, higher titled people tend to be preferred for the role). He has under him anywhere from two to a half dozen Pengliman, also local men, also elected, each with his own bailiwick within the perbekelan. Both Perbekel and Pengliman are paid, but not very well, by the Government according to the number of kitchens in their domain. As it is through them that the policy directives, propaganda exhortations, and social welfare activities of the Djakarta political elite filter down to the mass of the peasantry and from them that reports on local conditions start back up, they form a kind of rural civil service, a miniature administrative bureaucracy constructed out of local elements.

As might be expected, the arbitrarily drawn boundaries of perbekelan do not, save in the odd case, coincide with any other unit in Balinese society, past or present; rather, they group from four to ten hamlets into what seemed to logical, efficient Dutch administrators to be logical, efficient administrative units. The result is that the hamlets involved not only may have no traditional ties with one another but may even be traditionally antagonistic, while othtr hamlets of long and continuing association may be separated by perbekelan boundaries. The Perbekel is thus placed in a rather anomalous position for, although his superiors tend to regard him as a "village chief" and expect him to have important traditionally based executive powers, his constituents tend to regard him as a government clerk and consequently not directly concerned with local political processes at all, the direction of which they conceive to lie in the interlocked hands of the temple, hamlet, irrigation society, kin group, and voluntary organization chiefs. The Perbekel is not governing an organic unit, but one which in most cases feels rather little internal solidarity at all and, though he may have some traditional status in the particular hamlet within the perbekelan of which he himself happens to be a member, he is unlikely to have much in the others.

As the Indonesian state increases its activities in an attempt to bring the country into the modern world, the Perbekel both becomes more and more important and feels more and more keenly the uncertain nature of his position. The degree to which he is able to assert his role, to secure his dominance over traditional leadership in matters concerning the national state, and to make a true political unit of the perbekelan varies with several factors: whether or not he is energetic and intelligent, whether or not he is the descendent of a traditionallocal ruling family, whether or not his perbekelan happens to include hamlets having long-term bonds with one another, whether or not there are a number of young, educated men who will support and encourage his "modernization" efforts, and so on. As with the other planes described, the role of the perbekelan unit in rural Balinese social structure is not describable in terms of any static typological construct, but can only be seen as ranging over a certain set of organizational possibilities.

THREE BALINESE VILLAGES

Thus far in the analysis of Balinese rural social structure the concept "village" has been studiously avoided, mainly because it is used by the Balinese in several mutually contradictory ways. Sometimes "village" (desa, a Sanskrit loanword) is used as a synonym for bandjar (the basic rural political unit); sometimes to refer to the Kahyangan- Tiga (temple congregation); sometimes, especially by urbanites and government officials, to the region under a single Perbekel; and, perhaps most commonly, for a vaguely demarcated region in which the planes of organization intersect in such a way that the people living within the region have rather more ties with one another than they do with people in adjacent regions. In this last and rather fuzzy sense, "village" refers to the integrative as opposed to the analytic aspects of rural social structure, and it is in this sense that the term will be used here. A village is not a hamlet, a temple group, or a perbekelan, but a concrete example of the intersection of the various planes of social organization in a given, only broadly delimited locality.

1. Njalian.

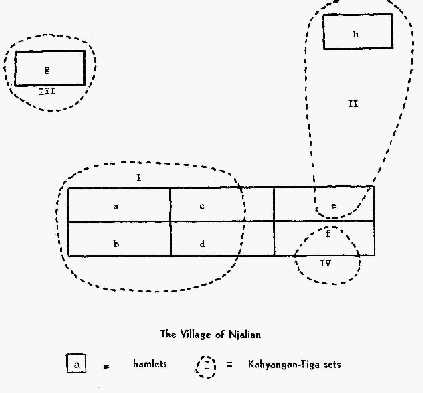

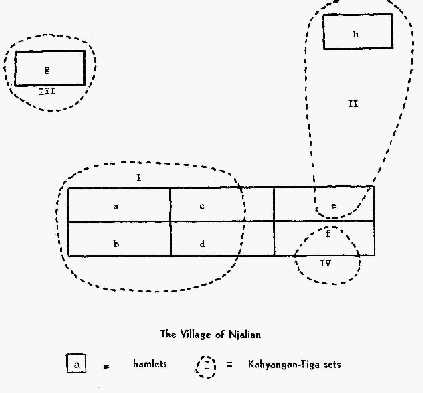

In pre-Dutch times the seat of a minor lord and a secondary market center, Njalian lies at the western edge of the former kingdom and present regency of Klungkung, and is one of the more complexly organized villages of Bali. In Njalian virtually nothing is coordinate with anything else and the crisscrossing of loyalties reaches an almost unbelievable degree of intricacy. The perbekelan of Njalian--the present Perbekel is the head of the traditional ruling house, a Tjokorda by title--contains the rather large number of about 3,000 kitchens distributed among eight hamlets, six contiguous within one large settlement cluster and two spatially isolated some two or three kilometers away. There are four sets of Kahyangan- Tiga temples. To one set belong the members of four of the contiguous hamlets, to a second set belong those of one hamlet in the main cluster and one of the segregated ones, to a third set belong only the members of the other isolated hamlet, and to the fourth only those of the other hamlet in the major cluster:

Even this rather involved diagram greatly oversimplifies the situation. In the first place, many people living in the territory of one hamlet are legally members of another. Further, the coordination of the temple sets with the hamlet boundaries is very recent, being instituted over strong opposition by the present Perbekel in 1950, and still very imperfect. Before the change, a man belonging to hamlet "a" would often belong to temple set IV, or a man in "e" to set I, and so on, and to some extent this still occurs, for traditional allegiances are difficult to reorganize by administrative fiat. Still further, the four bandjar in temple set I --"a", "b", "c", and "d"-- are not really territorial at all; though the meeting houses involved are distributed as shown, members of the hamlets attached to them are randomly interspersed through the whole a-b-c-d area. This sort of nonterritorial hamlet organization is actually frequent in Bali and was ignored above for purposes of descriptive simplicity. Finally, in Njalian the unit cooperating at a cremation--called a patus --is not coincident with the hamlet as it is in most other places. Instead, hamlet "a" is divided into two such collective work groups for cremations, "b" forms but one patus, "c" two, and so on. Thus a man may well have his hamlet alliance in one place (not even necessarily where he lives), his temple ties in a second, and his cremation obligations in yet a third, though of course in a majority of cases some of these affiliations may be merged.

Since Njalian contains representatives of a wide range of caste titles, the interaction of the status hierarchy with the hamlet and temple systems adds yet another dimension of complexity. Hamlet "a" consists entirely of Brahmana and higher Satria people, including the ruling family, but some lesser Triwangsa belong to "b," "c", "d", and "e", mixed in among the Sudra. Hamlets "f", "g", and "h" are wholly Sudra, with "f" consisting of but a single dadia kin group, a rather uncommon occurrence. Caste affects temple organization too. In temple set I the death temple was until two years ago divided by a low wall; the Sudra organized their festival separately and held it on one side of the wall, the Triwangsa held theirs on the other. But this has been changed for reasons of economy and democracy, and now all worship together. Voluntary organizations, of which there are literally dozens, irrigation societies, two main ones being involved in this area, and some thirty or forty kin groups also complicate social relationships, though kinship is evidently less important here as an organizing force than in many other villages.

In such an admittedly extreme case of cross-cutting social groupings, the problem of integration, of mutual adjustments among the groups, is a very pressing one. At times open fights have broken out between leaders of various groups over the question of who had prior rights on the services of members common to them. Heavy concurrent demands often mean that work is only hastily done; when the slit gong is beaten to call together members of a given group, many people fail to appear because they either were too far away to hear the gong or thought that it was being sounded for another group to which they were not obligated. To rationalize this situation the Perbekel has instituted a monthly meeting of all important group leaders--fifty people or soin which he tries valiantly to get them to coordinate their several efforts. He has also attempted to territorialize the system more by making hamlet and temple membership dependent on residence but, though he has had a little success in this direction, most of his efforts have been resisted by the villagers who, he claims, prefer things to be complicated. Despite the fact that he is the traditiomtl ruler of the area, that he has been Perbekel for thirty years, and that he now has the whole Indonesian State behind him, he says that there is really very little he can do in reforming village institutions. People bow and act subservient, but they do just as they wish.

2. Tihingan.

Although it lies only six miles or so east of Njalian, in the heart of the former kingdom of Klungkung, Tihingan differs from Njalia.n in most of its important features. Unlike Njalian, Tihingan has never been the seat of a lord, has relatively few Triwangsa and the Perbekel is a Sudra. Unlike Njalian, social affiliations, though complexly organized, are quite systematically integrated rather than randomly crosscutting. And unlike Njalian, there are within the perbekelan three definite spatial clusters of social loyalty to which the name village can be properly applied, while the perbekelan as a whole forms only the vaguest of social units. The three villages concerned are Pau, Penasan, and Tihingan proper (the seat of the Perbekel which, consequently, lends its name to the entire perbekelan). We shall be concerned here only with Tihingan proper.

Tihingan proper consists of a single hamlet of some 138 kitchens grouped into 85 house-compounds, and there is but one set of Kahyangan- Tiga temples to which all members of the hamlet belong, a rather un typically simple arrangement. There is a Brahmana priest living in the village, and there is a scattering of low-title Satria and Vesia families, but almost 90 percent of the population is Sudra. From the structural point of view, however, the most striking characteristic of Tihingan is neither its territorial pattern nor its status system, but the rather unusual importance of kinship as an organizational force in social life. It is the four dadia, accounting for nearly 80 percent of the village population, which form the axis around which Tihingan village life mainly revolves; and the implications of this simple fact can be traced through all the levels of its social organization, On the religious level, each major dadia owns a very large, handsomely carved temple (in the case of the two largest dadia, even larger and more handsomely carved than the theoretically superordinate Kahyangan- Tiga temples) near the center of the village. The upkeep of this temple and the carrying out of the requisite semi-annual ceremonies within it in suitable style are among the major functions of the dadia, and rivalries in those matters can become quite intense.

At the political level, the distribution of hamlet leadership roles is consciously and carefully designed to provide a realistic reflection of the balance of dadia power. There are five klian or chiefs. Four of these are chosen, one from each of the major dadia; the fifth klian at the same time holds the office of Pengliman and is a member of the second largest dadia. Since the Perbekel himself, a man of some weight within Tihingan proper, is a member of the largest dadia, the kin group foundation for local leadership is clear and exact. Further, in supra-village political processes, institutionalized in the party system of the "New Indonesia," the two largest kin groups are allied as a faction against the next two plus all the families not belonging to a dadia. All of the first group belong to the Socialist party and all of the second to the Nationalist, so that party allegiance is absolutely predictable from kin group membership, and reflects the internal organization of the village rather than personal ideological conviction.

On the economic level, each dadia forms a cooperative work group for the manufacture of Balinese musical instruments--me tall a phones, gongs, cymbals, etc.--a smithing craft in which this village is partially specialized; the personnel working in any given forge almost inevitably are members of the same dadia.10 Further, most tenancy and exchange work patterns in rice field cultivation also follow kin group lines, introducing these alliances into the irrigation society context as well. More informal economic relationships--money lending, patronage, and so on--follow the same pattern. Finally, even informal recreational interaction is shaped by extended kinship ties. It is only rarely that a man will enter the house-compound of a nonkinsman after nightfall when the most intensive gossiping takes place, though he will move freely among the yards of his dadia members. (A somewhat more consistent and literal adherence to the virilocal ideal in Tihingan than is common elsewhere means that house compounds of the same dadia tend to be fairly well clustered within the hamlet.) In cock fighting, a great part of the pattern of alliance and opposition--whose cock fights whose, who bets against whom, --is only explicable in kinship terms. In religion, politics, economics, and informal social interaction, kin group membership therefore has a primacy in Tihingan which, though it is far from representing a universal pattern in Bali, is, like Njalian's lattice-work structure, a realized example of one possibility intrinsic in the intersecting plane type of village organization.

In this type of village organization the dangers of factionalism are obvious and the problem of containing kin group loyalties within the bounds of affiliation in hamlet, irrigation society, temple group, and so on becomes acute. Public activities are often marked by partially concealed kin group antagonisms. For example, when the hereditary priest of the origin and death temples died without an heir ten years ago, the kin groups could not agree on his successor so that responsibility for the ceremonies in these temples now rotates among the priests of the four dadia temples--a highly unsatisfactory and irregular pattern that the people themselves regard as "not quite right, but better than having an open war." At hamlet meetings in the bale the sort of universal agreement necessary to make decisions is difficult to accomplish, so that many proposals are blocked by the opposition of a minority kin group. For example, when the Perbekel tried to convince the hamlet to change funeral customs so as to bury people immediately, even on an unlucky day, rather than keep the corpse in the house for several days (a government-suggested health reform that the neighboring bandjar had adopted with little difficulty) the opposition of the dadia most hostile to the Perbekel's prevented the change from taking place, although the majority of villagers were in favor of it. Antagonisms arising out of marriages and divorces across dadia lines, economic rivalries between the musical instrument manufacturing groups, and competitive prestige displays at dadia temple ceremonies also contributed to the heightening of this sort of intergroup tension.

Yet in general, the village is fairly well integrated and factionalization is usually kept within bounds.11 In part this is accomplished by the concurrent application of two explicit rules of procedure. The first rule is that whenever a group formed on the basis of one principle of affiliation is allocated a given social function, no other principle of affiliation may receive any recognition whatsoever. Thus if the hamlet is cooperating in some task, the work is never suborganized in terms of kinship, caste, or any other bond. If subgroups are technically necessary, people are grouped in a random manner, each family being regarded as a hamlet member pure and simple, as having no qualitative difference from any other. ("The hamlet knows no kinship," runs a Balinese proverb.) Similarly, when a dadia is working at a temple festival, or whatever, the sub-dadia ties within the dadia are considered to have no reality and do not act as a basis for subgroup differentiation.

The second rule sets forth a hierarchy of precedence in which the needs of the hamlet outrank those of the dadia, those of the dadia outrank those of the sub-dadia, and those of the sub-dadia outrank those of voluntary groups. For example, if the hamlet as a whole wishes to harvest the fields of its members, then it has priority. The whole bandjar must harvest and does so as a group, with no internal differentiation. If the hamlet doesn't wish to harvest--per decision of the hamlet meeting--then the dadia have next rights, unaffiliated families either banding together or yielding their rights to one or another of the dadia. If the dadia also decides not to harvest, then the sub-dadia may; if the sub-dadia have no immediate needs then the task is surrendered to voluntary groups. The combination of these two rules of procedure--one prohibiting multiple bases of affiliation for a single task, one establishing an order of precedence--acts as a major integrative mechanism in this otherwise rather faction-prone village.

3. Blaju.

Unlike Njalian, Blaju is not the name of a perbekelan, and unlike Tihingan, it is not the name of a fairly well defined village unit within a perbekelan. Rather, it is the name for a broadly defined region of about six square miles at the eastern edge of the Regency of Tabanan within which the influence of a particular ruling family was preponderant in the pre-Colonial period and to a great extent continues so today. As such, Blaju forms a minuscule state within a state, and its pattern of organization is characterized primarily by a stress on territoriality and caste (or title) as bases for social affiliation. Perhaps more than any other area of Bali, Blaju approaches the common stereotype of peasant social structure as being organized in terms of a pyramid of increasingly inclusive territorial units--barrios, villages, subdistricts, districts, and the like--each unit ruled by an attached political official of appropriate status. But, unfortunately for the sort of theory which would like to see in this system a survival of an "original" Balinese pattern from which all else could be adjudged a "deviation," this hierarchical territorialization is a quite recent phenomenon, occurring as a consciously motivated social innovation explicitly designed to intensify social integration.

The area commonly denominated as Blaju contains four perbekelan, three contiguous, one a kilometer or so to the north. The members of these four perbekelan--about 1500 kitchens--support a common set of Kahyangan- Tiga temples, a rather unusual circumstance, for commonly Kahyangan- Tiga congregations are usually smaller and are less extensive than a perbekelan. Within each of these perbekelan there are four hamlets, and each of these hamlets is further divided into from three to six territorial subunits called Hiran. A.kliran has arbitrarily fixed borders and each adult living within these borders is ipso facto a member of that kliran. It is the kliran, averaging eighteen to twenty kitchens, which performs most of the important day-to-day social functions, and it is the basic cooperative work unit in planting-harvesting, ritual, and the like, having its own independent treasury, rice shed, and meeting place. For larger and more important local tasks the klirans of one hamlet will fuse as a single unit; in the same way hamlets unite within perbekelan for affairs of government, and perbekelan unite within Blaju as a whole to support the Kahyangan- Tiga temples. As the irrigation societies in the Blaju area are small and land holdings are not so scattered, irrigation societies tend to be more or less informally identified with the perbekelan and hamlets closest to them, so that the whole system becomes territorialized through and through.

At the geographical center of this whole territorial complex, facing the market and the main crossroads, lies the "palace" (puri) of the ruling family, a walled-in, shabby-genteel complex of houseyards, temples, alleyways, and open courts about a city block square, tightly packed with more than five hundred people comprising a single Vesia-Ievel dadia. The head of this dadia, Anak Agung Ngurah Njoman, is at the same time customary law chief for the whole area of Blaju--i.e., the four perbekelan within the Kahyangan- Tiga set. Though largely an honorary position concerned with giving advice in matters of custom, this apical role symbolizes the continuing dominance of the ruling family in the area. At the perbekelan level, two of the four perberkel are from this family (one of them again being the Anak Agung himself), the other two being ranking Sudra with traditional ties to the "castle."

The role of this elite group is strengthened in many ways. First, unlike many Balinese aristocrats, the Blaju ruling family is not impoverished. About one-fifth of all rice land in the area is still in their hands (though it is owned individually, not collectively, within the dadia), and as almost all this land is sharecropped by Sudra tenants who also have corvee obligations to their landlords, traditional patron--dependent ties remain of central integrative importance. Second, although the members of the ruling dadia live all in one place and so should be members of a single hamlet according to the territorial system, they are by traditional practice distributed among the sixteen bandjar in more or less equalized groups. They are assigned bandjar membership independent of their residence so as to insure a voice (and an ear) for the ruling house in each locality and to strengthen the unity of the whole region. Third, there is in Blaju a major temple, rivaling the Kahyangan- Tiga in importance, which is supported exclusively by all the people in the region who bear Triwangsa, upper-caste titles, thus symbolizing the importance of status and serving to ally all the local high prestige groups with the ruling dadia in its largely successful effort to maintain the traditional stratification system unimpaired.

As noted, this rather neat integration of territorialism and status is not altogether a traditional matter, but stems in part at least from rather recent reforms. The kliran subhamlet pattern, the distinctive element in the whole system, was only instituted in 1940. At this time the hamlet system was very weak, kinship unimportant, and most village functions had fallen into the hands of voluntary seka groups. "People" felt--evidently under prodding from the aristocracy, which began to reassert its leadership at this time--that there were too many such groups, that they made for conflict, for a decrease in valuable public activities, and led to a kind of individualism. "The seka got rich, but the bandjar got poor." Thus all the sixteen hamlets decided at once to institute the kliran system and to ban voluntary organizations for all important functions. And when the Dutch left in 1941 the ruling family further intensified its efforts to strengthen the status system which had also been weakened in the general move toward a less organic society, producing the present pattern of organization. Territorialism in Blaju is thus not a simple survival from the distant past, but the outcome of the interaction between traditional values and the quite untraditional events of the twentieth century.

In such a system integrative strains are likely to appear across caste lines, and despite all the bowing and scraping one sees in Blaju, Sudra resentment against Triwangsa domination is quite evident. When a small Sudra dadia of Sunguhu which traditionally has the right to patronize priests appointed from among its own members rather than Brahmana ones, attempted to institute this system in Blaju a few years ago, they were expelled from their hamlet under intense Triwangsa pressure on the basis of "injuring local custom and denigrating the upper castes." Despite heavy pressures from the central bureaucracy and some local sympathy for the rebels, the Blaju upper castes held firm and the Sunguhu ultimately capitulated. But, irrespective of such strains, Blaju is rather more tightly knit than most Balinese villages: all the 1500 families were members of a single national political party, and one of the few really effective consumer-producer cooperatives in Bali was located in Blaju, its effectiveness being mainly attributable to the fact that it, too, had 100 per cent membership.

SOME THEORETICAL IMPLICATIONS

Of the many theoretical issues growing out of the analysis of Balinese village organization, among the most interesting are those centering around questions of typology. Typologizing has always been a central concern of social anthropology because both descriptive simplicity and comparative generalization rest on the possibility of summarizing social organizations in terms of constructs at once ethnographically circumstantial and formally distinctive. Whatever their shortcomings from more sophisticated theoretical perspectives, such types as "The Indian Village," "The Chinese State," or "The Nuer Kinship System" (to say nothing of "Peasant Society," or "Segmentary Social Organization," which are perhaps best seen as second order types of types) seem essential to comparative analysis of even the most rudimentary sort. But the Balinese case, in which this methodologically fundamental task of discriminating wood from trees seems unusually difficult of accomplishment, suggests that some of the assumptions underlying our usual typologizing procedures may be in need of revision. Particularly, and perhaps paradoxically, they suggest that clues to the typologically essential may as often lie in rare or unique phenomena as they do in common or typical ones; that essential form may be seen more adequately in terms of a range of variation than in terms of a fixed pattern from which deviant cases depart.

In general, two main approaches to the problem of constructing first order typologies of social organization within a given culture area have been common in anthropology: the "lowest common denominator" approach, and the "representative unit" approach. In the first of these, the procedure is to create a synthetic picture of "Eskimo Life," or "Tale Society," or "Chinese Culture" by taking the various forms found throughout the greater part of the respective culture areas and integrating them so as to provide a generalized account of social structure in an overall sense. Here the anthropologist concentrates on sorting out what is typical from what is not within the entire social field, and the result is a picture which describes directly no actual, given social unit, but which rather summarizes the sort of social form characteristic of the society at whatever point one chooses to look at it. In such a view, variations are interpreted as circumscribed deviations from the general pattern caused by locally acting forces of an ecological, historical, or acculturative nature. This is the older and more popular approacp of the two. It is the one usually taken by textbooks and simply descriptive monographs, by such summary volumes as Murdock's Our Primitive Contemporaries (1934), and for the most part by the British anthropologists in their African studies.

The "representative unit" approach might also be called the "Middletown" approach, because the procedure is to choose a concrete community--village, town, or tribal settlement--which is at least in a broad way "typical" of the sorts of community found within the culture area. Whether the choice is made on the basis of a systematic social and cultural survey of the whole area or in a more intuitive manner, the attempt is to find a community which forms a useful sample of the broader society, one in which idiosyncratic traits are few relative to those shared with other communities, and one in which most of the patterns deemed basic within the society generally are represented in a "normal" form. This procedure may be refined by choosing several such communities within subcultural areas, as in Steward's Puerto Rico study (Steward et al. 1956), but the methodological strategy is nevertheless the same: to choose a community which is to the greatest possible degree directly representative of more than itself.12

Both of these now established procedures yield rather strange results when applied to Bali. The lowest common denominator approach obviously depends on the possibility of finding some fairly simple fundamental patterns --a territorial village, a clan and lineage system, a developed caste structurewhich appear over and over again in various parts of the culture area in a broadly similar fashion. But in Bali, though certain patterns are common throughout the whole area the form in which they actually appear differs so widely that any synthetic picture must be drawn in such a generalized fashion as to have little substantial reality of any kind. One could easily enough construct a "Balinese village" with a "typical" temple setup, hamlet organization, kinship system, irrigation society, title distribution, and so on; but such a composite construct would utterly fail to express the two most fundamental characteristics of Balinese village organization, namely, that these patterns take widely differing forms from village to village, and that their relative importance within any particular village integration varies greatly. For similar reasons, the representative unit approach is also almost certain to be misleading. Are we to take Njalian, Tihingan, or Blaju as typical of Bali? In a direct descriptive sense they are not typical of much beyond themselves; but neither, probably, is any other Balinese village. If we are to discriminate what is really essential and characteristic in Balinese village organization we need to take a somewhat different tack and conceptualize that organization not in terms of invariance in overt structure throughout the whole island, or from place to place within it, but rather in terms of the range of overt structure which it is possible to generate out of a fixed set of elemental components. Form, in this view, is not a fundamental constancy amid distracting and adventitious variation, but rather a set of limits within which variation is contained.

What is common to Njalian, Tihingan, and Blaju, and to Balinese villages generally, is the set of planes of social organization out of which they are built up; it is the fact that they are all constructed, although in different ways, of the same materials which accounts for the strong family resemblance they show despite their great structural diversity. In the actual investigation of Balinese village organization, one of course proceeds in a direction diametrically opposite to the logic of presentation followed in this paper: the planes are derived through an inspection of a series of villages rather than discovered in pure form and then combined to generate villages. As more and more villages are studied it soon becomes clear that a relatively small set of basic elements is involved; after one has discriminated temple units, hamlets, irrigation societies, the title hierarchy, the kinship system, voluntary organizations, and governmental units-- he comes to feel that he is not likely to find a village in which one of these is wholly lacking nor one in which a completely new plane is present.13 But though the number and type of elements are thus fairly quickly discovered the possible forms they can take and the ways in which they can unite with the other elements are not. Almost every village studied reveals some new organizational potentiality with respect to one or .several of the planes, and a new mode of integration. The process of investigating Balinese village organization, in a typological sense, is therefore a process of progressive delimitation of the structural possibilities inherent in a set of fundamental social elements. What one derives is not a typical village in either the lowest common denominator or representative unit sense, but a differentiated and multidimensional social space within which actual Balinese village organizations are necessarily distributed. One discovers more and more what shapes a village can take and still be distinctively Balinese.

Among other things this means that the peculiar, the unique, and the odd take on a rather different significance than in the usual typologizing procedures, for they are seen not as exceptions to a general rule to be accounted for by ad hoc considerations which save the rule, but as providing valuable further clarification of the basic principles of social organization. From Njalian's crisscrossing structure we learn that the various component planes are to a very large degree independent of one another; from Tihingan we learn how the Balinese kinship system works when given full play and how the other planes then adapt to its dominance; from Blaju we learn what increased territorialism and a stress on caste imply for social integration. Each case we confront reveals something new about the implicit potentialities of the typological model we are constructing, sets new bounds on the range of variation possible within it; and it does so mainly not in terms of what is common but rather of what is unusual about it. In the same way that Cromwell has been adjudged the most typical Englishman of his time on the simple basis of his having been the oddest, so the general typological significance of any particular Balinese village lies primarily in its idiosyncracies.

NOTES

1 The field work upon which this study is based was carried out from August 1957 to July 1958, with a three month break from January to March 1958, under a grant from the social sciences section of the Rockefeller Foundation, administered by the Center for International Studies, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. I am indebted to my research assistant E. Rukasah of the Fakultas Pertanian in Bogor, Indonesia, and to my wife Hildred Geertz for significant contributions to this study. This paper was written during a fellowship at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences, and I am indebted to many of my colleagues at the Center for their criticism and comments on earlier drafts. For general views of Balinese culture, see Bateson and Mead (1942), Covarrubias (1936) and Korn (1936).

2 For a more detailed description of Balinese temple forms, see Covarrubias (1936).

3 A Balinese temple festival is described in detail in Belo (1953).

4 It is also a legal community in that all the people in a single Kahyangan- Tiga congregation follow the same general rules regarding hamlet membership, marriage, inheritance, cooperative work, etc., rules which differ in detail from Kahyangan-Tiga group to Kahyangan-Tiga group. Sometimes this law community is headed by a Bendesa Adat, or customary law chief, who gives advice and direction on problems of custom. But, again, it is only in the odd case that this customary law community happens to coincide with a concrete political community.

5 Total Balinese population for 1954 is estimated at 1,500,000, with a mean density around 700 per square mile. In the thickly settled areas of South Bali densities reach up over 1,500 per square mile (Raka 1955).

6 In the Tabanan area bale are lacking in most hamlets, meetings being held in the open air beneath a banyan tree or in a temple courtyard.

7 For descriptions of these ceremonies, see Covarrubias (1936).

8 Only a minority of Sudra, considered to have higher prestige than the mass because of former affinal or political ties to higher status groups, have true address and reference titles. Most Sudra have no address title at all.

9 In most Balinese villages, marriage is preferentially within the dadia and, if possible, with the father's brother's daughter.

10 Economic specialization by village still persists to some degree in Bali, and is another factor to be considered in a full analysis of variation in Balinese village structure. It has been ignored here in favor of more formal considerations only for the sake of simplicity.

11 The only time it has threatened to get completely out of bounds was at the time of the Indonesian general elections in 1955 when each of the two factions went armed in fear of massacre by the other, but no actual violence occurred.

12 There is a third approach to typologizing, which is particularly prevalent in Dutch studies of Bali (Korn 1936), in which a community is chosen for study not so much on the basis of its representativeness in a statistical sense, but rather because it is held to show prototypical forms and patterns in a relatively uncomplicated, direct, and undistorted fashion. Highly traditionalized communities which have been relatively isolated from acculturative contacts are considered to have changed more slowly than other communities and so are favored as providing pictures of underlying social structures which are clouded over by adventitious elements in the more dynamic communities. This approach has tended to lose favor as it has become apparent that it is based on a dubious theory of social change and that the traditionalism of isolated communities is as often interpretable as an adaptation to peculiar environmental circumstances as it is a persistence of earlier and more fundamental patterns.

13 There is a handful of the so-called Bali Aga ("original Balinese") villages whose organization differs markedly from those of the overwhelming majority, having age groups, a gerontocratic political structure, communal land tenure, etc. Though the significance of these villages from an ethnohistorical point of view is an interesting problem, their position within Balinese society generally is marginal in the extreme. For descriptions of such villages, see Bukian (1936), Korn (1933), and Bateson and Mead (1942).

REFERENCES CITED

BATESON,

G., and M. MEAD

1942 Balinese character: A photographic analysis. New York, New

York Academy of Sciences.

BELO,

J.

1953 Bali: Temple festival. Monographs of the American Ethnological Society,

XXII, Locust Valley, New York.

BUKIAN,

I DEWA PUTU

1936 "Kajoe Bihi, Een Oud-Balische Bergdesa," bewerkt dor

C. J. Grader. Tijdschrift v.d. Bataavische Genootschaap, LXXVI.

COVARRUBIAS,

M.

1936 Island of Bali. New York, Alfred A. Knopf.

KORN,

V. E.

1933 De Dorpsrepubliek Tnganan Pagringsingan, Kirtya Liefrinck van der

Tuuk. Singaradja,

Bali. 1936 Het Adatrecht van Bali (Second revised edition). s'Gravenhage.

MURDOCK,

G. P.

1934 Our primitive contemporaries. New York, Macmillan.

RAKA,

I GUSTI GDE

1955 Monographi Pulau Bali. Djakarta, Indonesian Republic, Ministry

of Agriculture.

STEWARD,

J., et al.

1956 The people of Puerto Rico. Urbana, University of Illinois Press.

Form and variation in Balinese village structure, in: American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 61, No.6 (Dec., 1959), pp. 991-1012.

online source: http://www.jstor.org

JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

American Anthropologist is currently published by American Anthropological Association. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/anthro.html.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission.

Using this text is also subject to the general HyperGeertz-Copyright-regulations based on Austrian copyright-law (2001), which - in short - allow a personal, nonprofit & educational (all must apply) use of material stored in data bases, including a restricted redistribution of such material, if this is also for nonprofit purposes and restricted to the scientific community (both must apply), and if full and accurate attribution to the author, original source and date of publication, web location(s) or originating list(s) is given ("fair-use-restriction"). Any other use transgressing this restriction is subject to a direct agreement between a subsequent user and the holder of the original copyright(s) as indicated by the source(s). HyperGeertz@WorldCatalogue cannot be held responsible for any neglection of these regulations and will impose such a responsibility on any unlawful user.

Each copy of any part of a transmission of a HyperGeertz-Text must therefore contain this same copyright notice as it appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission, including any specific copyright notice as indicated above by the original copyright holder and/ or the previous online source(s).